The Mystery and Mastery of Tan Yeok Nee (Part 9)

In the mid 19th-century the Qing government’s first-hand knowledge of the outside world was notoriously thin. The last post told the story of their tardy awakening to the reality of the burgeoning wealth among Asia’s overseas Chinese communities and described how an imperial consulate came to be first established in Singapore.

Some contend that the Qing consulate was there to show “care and concern for the overseas Chinese, cracking down on illegal sale of cheap labours, protecting women, and tacking (sic) the pirates problem in the region”. The Qing History Society (Singapore) goes on to suggest that the first Qing Consul to Singapore, Zuo Bin Long, “served selflessly for the overseas Chinese, work (sic) hard to protect and ensure their welfare, as well as promoting education and setting up schools for them”. It is easy to be skeptical, even cycnical, when it comes to the mandate of individual consulate officials. But more generally, it is hard to believe that the Manchu Qing were prioritising the welfare of its former Chinese subjects in Singapore. During the final decades of their rule the Qing showed little interest, if any, in promoting the welfare of their Chinese subjects within its own domain, let alone anywhere else.

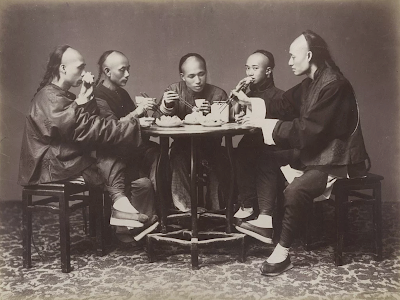

In a demonstration of their subservience to the Manchu Qing, Chinese men were required to adopt the “queue” hairstyle or else risk decapitation. However, many continued the practise even after they were beyond the grasp of the Qing authorities, suggesting that it may have morphed into something akin to self identity or even collective conciousness.

On the other hand, however, there is ample evidence that one of the main goals of the new Qing consulate in Singapore was the sale of Qing titles and honours to the local Chinese population: they announced as much in the press. While vanity and status on the part of the purchasers were undoubtedly important factors in the case of most transactions, the possibility remains that some philanthropically minded overseas Chinese made genuine and generous donations for the purpose of helping the victims of famine and flooding in China. In which of these two camps did Tan Yeok Nee sit?

Selfless or Self-Serving?

Did Tan Yeok Nee succumb to his vanity and purchase his Qing honours as did so many of his peers? Or, were they bestowed upon him in recognition of a genuine act of charity and compassion for the victims of the Northern Chinese Famine of 1876-1879 as has been suggested? It is a question worth asking because the answer would not only shed light on his character but also lend perspective to his standing and reputation in society. Tan’s story so far has revealed nuances that can be interpreted as differentiating him from many other high profile Chinese settlers in the region. Anyone seeking to confirm or challenge this notion, perhaps in order to better understand his character, should therefore be taking note.

When contemplating whether Tan was motivated primarily to help the starving, or to obtain a Qing title, the first thing to consider is the timing. Tan’s award was made ostensibly in recognition of a large donation he made to help the victims of the Northern Chinese Famine in 1876-1879. While honours for cash had been around for decades, perhaps centuries, the first part of the famine period predates the time of the Qing consulate in Singapore. It was only much later that the Qing started to ramp up the practise of selling titles with the consulate as the main vehicle utilized to target the Singapore and Malaya overseas Chinese.

As far as the famine was concerned the Qing court were preoccupied. The co-empress dowagers had just orchestrated a major palace coup. The Qing government’s response to the famine was further delayed by corruption and logistical challenges. Both of these factors undermined their relief efforts. In addition, many court officials were deeply suspicious of the intent of the foreign relief workers who were active in providing assistance relatively early on in the crisis. It is well known, for example, that most of the initial relief efforts were organized by private individuals such as Timothy Richard, Arthur Henderson Smith and William Scott Ament who were also missionaries. They appealed for help using colonial networks to access foreign communities in both China and the rest of Asia. They solicited donations and organized their administration and distribution, although their efforts were understandably limited in scope and reach.

It is quite possible given Tan’s status and, perhaps more so that of his sovereign Abu Bakar, that he would have made use of the more reliable channels to donate. It would have been reckless, perhaps even foolish, to place a large charitable donation into the shaky, inefficient and corrupt hands of the Qing officials. Tan was neither reckless nor foolish. Expediency may have pushed Tan to make use of the colonial structures, of which he was somewhat a part, to provide assistance to those in need as quickly as possible. These timing considerations suggest that Tan’s intentions were indeed to help the suffering, rather than to simply buy a title from the Qing court. At the time the cash-for-honours bandwagon may not have had enough momentum to accommodate people jumping onto it.

Evidence supporting Tan's sense of altruism do not depend on timing considerations alone. While Yen points out that many purchasers were out to impress, it is clear that Tan had no need for such grandstanding. He already had unassailable status and prestige. The Qing will have quickly realized that unlike other overseas Chinese to be found in Singapore and Malaya, Tan was a senior offical of, and represented, the monarch of an independent sovereign state. He had no need of a title to recognize and confirm his status within his community. He was fiercely loyal to Maharaja Abu Bakar and in return Tan enjoyed his steadfast royal patronage. He was not only a royal public servant but also part of the royal family. This was far more important to him than anything that could be bestowed by the Qing, the British or by any other outside power. In the mid 1890s the only Chinese in Singapore who had received a British title was Hoo Ah Kay, otherwise known as Whampoa. Similarly, Tan Yeok Nee was the only Chinese who had received a Malay title from the independent state of Johor. In the local context such honours were far more valuable than the ones that could be bought at a discount from the traveling salesman and occasional diplomats representing the Qing court.

Lastly, if Tan did purchase his Qing title for the sole purpose of status and prestige then it doesn’t appear to have added much to his already glowing reputation, at least not in Singapore where his fellow overseas Chinese jostled for status within their local communities. Yen Ching-Hwang’s research findings on this topic do not mention of Tan Yeok Nee, despite identifying by name at least 30 or 40 prominent and wealthy Chinese in Singapore and Malaya who did purchase titles. That does not, of course, mean that Tan wasn’t among the more wealthy Chinese merchants whose names were often reported in the Lau Pat newspaper over the years as recipients of Qing honours. It might just mean that for some reason Yen did not consider Tan a significant enough personality for him to be identified as one of their ilk. Given Tan’s wealth and status, this seems unlikely but it is, admittedly, a possibility.

Nevertheless, timing and other considerations aside, it is highly likely that Tan would have wanted to ensure the Qing were aware of his generosity, even if he hadn't participated in their scheme. There may have been other reasons that compelled Tan to make the Qing aware of what he was doing.

A Mind on the Horizon

This analysis has so far concentrated mainly on the Qing sale of honours to overseas Chinese and the story of how this unfolded in Singapore and Malaya. However, at this time Tan was probably thinking more broadly and strategically about his future than he had done over the past 40 years or so. As he planned and then built Zi Zheng Di he was thinking more and more about the distant land of his birth. The case for Tan Yeok Nee harbouring a heartfelt sense of compassion in providing famine relief looks more convincing with this context, especially if the alternative explanation was an urge to participate in a transactional cash-for-honours scheme. However, there is another dimension to the context which may lend some further weight this idea.

In 1883 Maharaja Abu Bakar undertook his momentous East Asian tour (the tour and its significance are key events described in Palace of Ghosts). Tan probably accompanied the Maharaja on at least the part of the tour that took him and his entourage to the southern Chinese port cities. There were likely other occasions too, both before and after this date, that Tan – either with or without Abu Bakar – embarked on trips to southern China. Maritime traffic between Singapore and China’s southern port cities had increased dramatically during the last two decades of the 19th century. It included to the Chinese “treaty port” of Shantou, (referring to the 1858 Treaty of Tianjin which opened the port city of Shantou – at the time known to foreigners as Swatow – to Western trade), about 300 km eastwards from Hong Kong along the coast of Guangdong province.

Shantou was just 20 km away from Tan’s hometown. Tan certainly made the trip several times but there is also the intriguing possibility that Maharaja Abu Bakar may have even visited Zi Zheng Di at Tan’s invitation, which by the time of his 1883 stop off in Hong Kong would have been very close to completion. It should be also noted that the recognition and title Tan received from the Qing court was bestowed upon him at about this time.

A 1915 map of Shantou (then known to foreigners as Swatow) showing it as an island. It includes an inset map showing the delta to the north, in the middle of which was Jinsha, the village of Tan Yeok Nee’s birth.

Mainland Chinese sources provide two intriguing points of interest. The first that Tan was indeed making frequent visits to China during this period. This makes sense since he was very hands-on in the creation of Zi Zheng Di. The second was that he was acting as Maharaja Abu Bakar’s de facto ambassador to the Qing court. Normally a small, only recently recognized state like Johor would not register on the Qing radar. But its association with the British must have caught their attention. In fact, Maharaja Abu Bakar was getting noticed by royal courts everywhere. He was, after all, an independent monarch, who in due course, was recognized by Queen Victoria of Britain, hosted by the German Kaiser and even received by Emperor Hirohito of Japan. Tan, apart from being obviously wealthy, was Maharaja’s Abu Bakar’s top official and, being Chinese, was a potentially a convenient conduit for the Qing court. For this reason alone, he was most certainly in a different consideration set from most other overseas Chinese. But, if true, why is it not a matter of historical record? The reason is because the Maharaja and Tan would have certainly suppressed this information to anyone outside of the Qing government. Such recognition and status would have angered the British colonial establishment which demanded control of the foreign affairs of states within their sphere of influence, regardless as to whether they were independent or not. If the British perceived any kind of interference by the Maharaja in their foreign affairs, especially as it concerned the Qing, there would have had serious consequences for Johor’s independence.

Tan, for his part, may have been thinking about connections to the Qing court from a completely different angle. He would have had memories from the times of his departure when emigration was illegal. He may well have had concerns about his legal status in the Qing empire. There may have been the possibility gnawing on Tan’s mind that having left China without permission from the authorities he might not be allowed back in. There were cultural nuances too. Safeguarding a reputation worthy of redemption was all important; but the shame of abandoning his family aside, Tan’s cultural context will have made him well aware of the deeply set sentiment that to leave the Chinese world was to cut oneself off from civilization. It was a potentially worrisome scenario that he faced.

Tan was not the kind of person who took unnecessary risks. Despite his good intentions he must have known that the court in Peking was on the look-out for wealthy individuals to contribute funds. Tan was ready to step up. His charity, at least in my opinion, was undoubtedly a humanitarian act that might have saved lives, but could have been self-serving too. Tan clearly understood that such a gesture would ensure his homecoming would not run into any hurdles, with fawning local officials cowering before Tan’s official statement of gratitude from the Empress Dowager Cixi and bestowment of a Qing official title of rank. To be acknowledged as a high-ranking official was highly desirable and awareness of someone’s bureaucratic rank was always widespread. Rather than feeding some sense of ego, Tan may have paid his money, through whichever channel, and in addition to helping the famine victims may have also received the Qing court’s endorsement and thus, at least by his reckoning, “approval” for his smooth return to the motherland. His donation will have ensured a hassle free retirement to his hometown. If there was a direct or indirect link between his donation and his title, the purpose is likely to have been to facilitate his homecoming rather than feeding a sense of ego or promoting his status among his peers.

"Just One More Thing...."

There is no satisfying closure to this attempt at historical detective work, at least not yet. There is plenty of smoke, but the fire is not clearly visible. The whole idea of Tan having some kind of connection to the Qing court in its final, self-destructive years is fascinating and certainly warrants further investigation. In the end it may be impossible to truly understand the exact nature of Tan’s relationship to the Qing court. What evidence there is suggests both overt and covert contacts between Tan and court officials. Much of the speculation above is supported by mainland Chinese sources which say that Tan acted as an ambassador. Although hard evidence is lacking it is also worth considering what happened to Tan’s second son, Chen Jin Fan.

One thing that Yen Ching-Hwang is unequivocal about is that:

“It is notable that all purchases were confined to brevet honours. There was no sale of office, and even the Kung-shen and Chien sheng degrees which were the most commonly sold in China, had to be changed to mere brevet. Overseas Chinese, though their financial assistance was needed in China, were still discriminated against by the Ch’ing government, perhaps from a shortage of offices as well as for traditional reasons.”

In fact, Chen Jin Fan, whose own house in Jinsha was located behind his fathers, went on to become an official in the Qing imperial court, and was appointed Prefect of Nakang in Jiangxi province. This suggest two things: firstly, that Chen Jin Fan took and passed the imperial examinations and was considered to have sufficient pedigree to secure himself the relatively prestigious position of Prefect; secondly, that his father Tan was genuinely held in high esteem by Qing officials and was not seen as just another overseas, nouveau riche upstart. He was not someone who could be easily enticed with frivolous decorations, nor easily separated from his money with the lure of a hollow title. In the dying days of the dynasty, therefore, Tan seems to have achieved some meaningful recognition and respect from the Qing. There is usually a sequence of events that leads to an outcome, and while we might not always have visibility on the details of the process, sometimes the outcome speaks for itself.

Comments

Post a Comment