What's in a Name: the Meaning of Tyersall

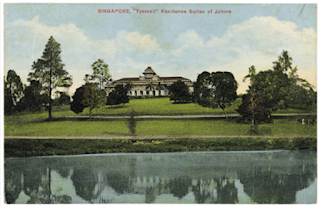

A turn of the 20th century Singapore postcard showing Tyersall Palace, or Istana Tyersall

Most people, as they go about their daily business in Singapore, pay little attention to road names other than remembering where they are for one reason or another. Some may make a mental note that it is a Chinese, Malay, or Tamil-sounding name or one that is left over from colonial times. For a few people, such as Brenda Yeoh, a Professor of Social Sciences at the National University of Singapore and author of several books on the subject, road names are a consuming passion. She has written extensively on the topic including Street Names in Colonial Singapore (1992) and Street-Naming and Nation-Building: Toponymic Inscriptions of Nationhood in Singapore (1996). Such books offer a fascinating spyglass through which to better understand urban history.

About a quarter of all road names in Singapore today bear names which tie back to the British colonial period, when roads were first laid down on the island. George Coleman, often cited as Singapore’s first architect and best friend of William Napier, was also very much involved in road construction. It was perhaps a less glamorous part of his job, one that involved the use of convict labour, but certainly of great importance to the early development of the city. These early roads often bore the names of figures in the community and indeed, Coleman Street, located in one of the oldest parts of urban Singapore, is the road on which he built his enormous residence–Coleman House–in 1823. (After Coleman’s death this building became the world-famous Hotel de la Paix in 1856, and then later in the 1880s, the personal residence of one of Sultan Abu Bakar’s closest advisors, Tan Hiok Nee).

Orchard Road is, of course, named after the orchards that could once be found along its route. It leads to the Tanglin district where further plantations could be found. Many of the roads in the Tanglin area today bear the names of the owners of the plantations which once stood there. The roads were originally tracks used by planters and workers to move around the plantation. Examples include Oxley Rise, Claymore Hill and Cairnhill Road. Other left-over colonial names refer to their original use (e.g. Boat Quay) or their location (e.g. Beach Road, although the beach itself was covered by reclaimed land long ago). Lastly, a small portion of Singapore’s roads refer to places or people in Britain, Queens Road being among the most obvious and referring to Britain’s Queen Victoria.

One road in Tanglin may, at first, appear to fall into this category of being linked to Singapore’s colonial past. Tyersall Avenue begins at its junction with Holland Road and heads north, changing name to become Tyersall Road after the junction with Gallop Road. Further along, the road changes name again to become Cluny Park Road. By process of elimination, you may reasonably deduce that since “Tyersall” does not seem to be of Chinese, Malay or Tamil origin, there must, therefore, be an old colonial connection–the word certainly sounds like it has an English provenance. However, a search of colonial figures in the 19th and early 20th century reveals that no such figures by that name existed. So, then, what if we move the search to colonial-era Britain? Once again nothing significant crops up that would suggest it was named after a distant place or person residing on the other side of the planet. An enquiry submitted to a local Singapore toponymic expert would quickly deliver the answer: it is, of course, named after Tyersall Palace, or Istana Tyersall, which used to stand to the west of today’s Tyersall Avenue and via which it could be reached.

Istana Tyersall is the palace in the title of my book Palace of Ghosts: How a Global City Gave Birth to a Royal Dynasty. It was one of two palaces that stood on the large plot of land bordered to its east by Tyersall Avenue. Antique maps show that should you have wanted to visit the palaces you would have needed to travel along either Tyersall Avenue or Tyersall Road to reach one of the entrances to the park where the two palaces stood. So, the mystery is solved–or is it? This explanation links the road name to a building of the same name, but it still does not tell us what the name actually means. In addition, the owner of the building was Malay, not English. So, not only is the meaning still unknown, but so is the reason a Malay property owner gave his residence a name that sounds distinctly un-Malay?

As with many things to do with the story of Tyersall, the very name remains a mystery. As noted, with the absence of any colonial figures named Tyersall, the temptation is to assume that the name is linked to another place, probably in Britain. However, after an extensive search only one place with a similar name can be found–a tiny, relatively unheard-of village in West Yorkshire, in Northern England. When Istana Tyersall was built in the late 19th century the “village” was little more than a small farm cottage and it is also spelt slightly differently, with only a single letter “l”–Tyersal. The possibility that Istana Tyersall’s owner, Sultan Abu Bakar, would know of this place, or that any of his friends or family would know either, and even if they did, why on earth he would name his palace after such an obscure place, renders the idea absurd.

Sultan Abu Bakar was detail-oriented. He never did anything without full clarity on, and understanding of, the reasons he was doing it, as well as consideration of the possible consequences of his actions. The house he bought from William Napier was called Tang Leng, and so the decision to rename it would not have been made on a whim. When he bought it, he already had plans to knock it down and rebuild it, even though he continued to live in the old house for some years before beginning this project. The new name would have therefore been purposefully chosen with his longer-term intentions in mind. Why then did he choose the name “Tyersall” for his new grand home that would eventually be recreated as a grand palace?

Just for fun, let’s have a go at trying to break down the word to try and find its meaning. The first syllable, Tyre, could refer to the nearly 3,000-year-old Phoenician city of Tyre located in what is now south Lebanon. People from Tyre established the great city of Carthage in North Africa in ancient times. Could it be that Sultan Abu Bakar wanted to link his palace to the grandeur and mystery of ancient Mediterranean history? Possibly, but unlikely. The western mind is quite tuned into ancient Mediterranean history as part of its cultural context. For Sultan Abu Bakar, despite being often described as an Anglofile, his cultural context was Malay tradition, not ancient Mediterranean civilization. It’s probably not the primary reason for choosing the name but who knows, it could be interpreted as being evocative of the grandeur of ancient majesty.

Next, then, what does Tyre mean in Sultan Abu Bakar’s native Malay? Well, nothing, exactly: but “Tir” means “rook” or “castle”, as in the chess piece. The word “rook” comes from the Persian word “rukh”, meaning chariot, as this piece was known in predecessor sets of chess pieces in India. These Indian chariots had large walled structures on them, resembling a moving castle. Sultan Abu Bakar would no doubt have learned to play chess at the school he attended, Telok Blangah Malay, which was managed by the Reverend Benjamin Peach Keasberry. There, among other things, he was instructed in English manners, customs and etiquette. Almost certainly he was taught to play chess, as every English educated school boy was at the time. While thinking about the name for his palace Abu Bakar must have been attracted to the idea of his residence being seen as a castle.

Then what of the second syllable “all”? We have to remember that when Sultan Abu Bakar purchased the second plot of land adjoining that which he had already purchased from William Napier, there was already a fine mansion standing there. It was the one built by Captain John Dill Ross which he had named Woodneuk. As we know “neuk” is a double entendre. The more respectable of its two meanings is “hideaway” or “cosy corner” in the Scottish language. In English, the equivalent word used in place names is the old English word Halh: this means “corner” or “hollow” or “nook”, the latter being the exact English equivalent of the Scottish word “neuk”. It’s quite possible, then, that to pair the two buildings that now sat on the same property, Sultan Abu Bakar borrowed the second syllable of Woodneuk, used its English place name equivalent of Halh, and combined it with the Malay word for castle, Tir, to create “Tirhalh”: “castle corner”. It would have contrasted with his adjacent smaller property “Woodneuk”–meaning “wooded corner”. He may have then anglicized and modernized the combined word to come up with “Tyersall”. It’s just a bit of fun speculating, but if anyone has a better explanation, I would love to hear about it.

Comments

Post a Comment