William Napier and the Labuan Misadventure

The island of Labuan in todays West Malaysia was, along with Singapore, once part of the Straits Settlements. Although, in itself, it is not a part of the story of Palace of Ghosts, events connected to it were to play a role in some of the important outcomes in the story.

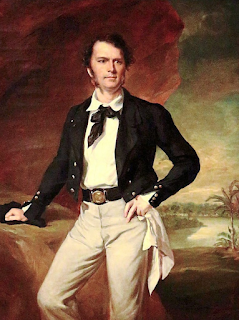

As told in an earlier posting, William Napier is one of the key characters appearing early in the story of Palace of Ghosts. He made two sojourns in Singapore and the catalyst for his second visit was when the tiny island of Labuan became a Crown Colony of Britain in 1846. Today, few people outside of Malaysia, and many of those within it, know much about the place, if anything. It is safe to say that William Napier probably wished he had also never heard of it either, or even better, wished he had never even set foot on it. Napier’s Labuan misadventure is not a vital element of the central narrative of Palace of Ghosts and is therefore largely omitted from the book. However, there are several threads that link the episode to some of the plot elements that are important to the story–points of interest or coincidences rather than core plot elements.

A small island sitting off the coast of northwest Borneo about 900km northeast of Singapore, Britain had previously turned down an offer from the Sultan of Brunei to set up a base there. At the time, the British and the Sultan of Brunei were both cooperating to combat piracy in north Borneo and the Sulu islands (now part of the Philippines). However, with enthusiastic cheerleading from James Brooke, Britain’s most well-known colonial adventurer in the region, it was ceded by Brunei in 1846, apparently under pressure, to Britain in the Treaty of Labuan. This in itself is a controversy. Many claim that the Sultan of Brunei was forced to cede the island, and it may well be that certain local British actors did in fact make a show of force. But that colonial zeal was certainly not shared by the powers that be in London. It is also an interesting example of muddled colonial thinking that is now largely forgotten. It’s probable that what was communicated to London by local British, including James Brooke, was not 100% factual; and similarly, what was communicated back from London, may not have been followed to the letter.

In 1848, Brooke became its first Governor. He was in London at the time and quickly began to assemble a team to administer the new territory. It was widely believed that the island had valuable coal deposits and was touted as the next Singapore. William Napier was in London when these events unfolded and was well acquainted with Brooke and the colonial establishment generally. He was well known as a former leading community figure and successful businessman in Singapore. He was, therefore, in immediate contention for a role in the new colony of Labuan. There were few others who could claim such deep knowledge and experience of the region. He was, therefore, an obvious choice for Brooke to make in appointing him Lieutenant-Governor of Labuan.

The Signing of the Treaty of Labuan

Napier was flattered, so much so that he even named his new-born son after James Brooke: James Brooke Napier! Captain Henry Keppel was instructed to transport the new administrative contingent to Labuan, via Singapore, on board the steamship HMS Meander. Also on board with Napier and Brooke was the former’s wife, Maria Frances, his adopted son George, his probably adopted Eurasian daughter Catherine, in addition to the infant James Brooke Napier. On the way, Catherine married another passenger on board Mr. Hugh Low, also a member of the Labuan party on his way to take up the post of Colonial Secretary of Labuan.

There was much excitement among European society about the arrival of HMS Meander in Singapore on 20th May 1848 with its party of celebrity passengers and captain. Captain Keppel, although at a still relatively early stage of his long and illustrious career, had won plaudits for his operations against the Borneo pirates just a couple of years earlier and had become a hero of colonial society as a result. Brooke, of course, held mega-star status as the white Raja of Sarawak and represented everything the most ardent colonialists held dear to their hearts. For Napier, it was a kind of homecoming: he had been away from Singapore for about two years and was fondly remembered, respected and held in the highest esteem.

The excitement ratcheted up a few notches when it became known, upon the party’s arrival, that Napier had been asked by Britain’s Queen Victoria and Prince Albert to represent the crown and bestow upon Brooke the honour of KCG–a knighthood, in other words.

The event was to take place at the Masonic Lodge that Napier himself had established when he previously resided in Singapore during 1845 and was to be held on the most auspicious date of the Feast of St John the Baptist. It was to be an occasion of utmost solemnity with Singapore society’s leaders invited as guests of honour. Napier, now Lieutenant-Governor of Labuan, sat next to Captain Keppel at the lead table for dinner as the ceremonies got underway.

One of the most prominent figures in Singapore society at the time, Mr W.H. Read, had his letter published in The Singapore Free Press soon after:

“Mr Napier was an old resident in Singapore, and a general favourite; but his peculiar way of carrying his head, of brushing his hair, and swagger of body, had earned him the title of ‘Royal Billy’. Fully impressed with the importance of the functions he had to perform (and perhaps a little bit more than was necessary), the Lieut-Governor endossed his uniform, begirt himself with his sword, and was marshalled into the room prepared for the ceremony, in ‘due and ample form.’ His head was higher than ever, his hair more wavy, and with the strut of a tragedy tyrant, he proceeded to mount the steps of dais, and, to the horror of the assembled spectators, sat down on the Royal Throne. There was a general titter; whether the drama was a result of an overreaction to the occasion or a sense of pride or solemnity, or humour, the moment was equally matched by Brooke himself in receiving the honour. The breach of protocol, if that is what is how it might be described was soon forgotten. Napier’s reputation as a friendly, generous, knowledgeable and highly respected member of the community won the day.”

The whole event was considered as Singapore’s biggest moment since Raffles departed 25 years earlier. After the ceremony, a ball was held at the Government House to which 150 guests were invited. It was the party of the season with lively, excited dancing until after midnight, rounded off by supper and a fireworks display to which representatives from the local communities were invited into the grounds. The Eastern Archipelago Company was set up that year with a paid-in capital of some $200,000 for the purpose of developing the trade of the Labuan and settlers were invited to arrive after the 1st of August. An office of the Labuan Government was set up in Singapore.

Napier was back, side by side with one of the most admired heroes of the age, at least among the colonialists, and representing Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom and Empress of India. It was a stunning return that enhanced his already distinguished reputation in Singapore society. He may well have felt justified in the view that he was at the top of his game.

The unbridled optimism was not to last long. William Napier’s only term in public office was a disaster. His job as Lieutenant-Governor of Labuan, a position he held for less than 2 years beginning in April 1848, had few positive outcomes. Although an accomplished businessman, newspaper editor, and philanthropist, he had little, if any, experience in public administration. To make matters worse, the colony of Labuan was one of the least developed and with the least potential and resources in the British Empire. One of the reasons for its lack of development was that it was newly acquired and Napier was its first Lieutenant-Governor. Despite Napier’s initial enthusiasm for both the role and his new boss, Governor James Brooke the White Raja of Sarawak, it was not long before reality kicked in. There was no usable coal and as a potential trading hub, it was a far cry from what Singapore had achieved in its short time.

Moreover, Brooke was notorious for being an exceptionally difficult man to work with. One can only assume that Napier had no idea what he was getting himself into. Napier, frustrated with the lack of resources, unhelpful and demotivated colleagues, a general malaise and widespread malaria throughout the colony led to him falling out with just about everyone. Getting anything done seemed to be close to impossible. Eventually, he argued with Brooke himself and the relationship broke down irretrievably. Brooke dismissed Napier on the dubious charge of borrowing money.

Napier left and headed back to Singapore for what would turn out to be his second sojourn there. Labuan had been a disaster for him from a career perspective but also personally. The whole Labuan misadventure would eventually claim the lives of three of his family members. That part of the story may be found in Palace of Ghosts. The net result, however, was that it had brought him back to Singapore and therefore set the wheels in motion for the important role he was to play in the events that subsequently transpired.

The Labuan episode was notable because it brought back Napier to Asia, and because of his run-in with Brooke who would later find himself at the centre of an international controversy, during which Napier was asked to testify against him. However, it’s also notable because it brought Captain Henry Keppel back. Although Keppel does not make an appearance in Palace of Ghosts, he has some bearing on the story beyond just captaining the HMS Meander that brought Napier back to Asia.

***

Henry Keppel (1809-1904), later Sir Henry Keppel, Admiral of the Fleet, was to become one of Britain’s best-known and most distinguished figures in the British Royal Navy. He was the first and principal Naval Aide-de-Camp to Queen Victoria and a favourite and friend of King Edward VII who succeeded her.

As Captain of the HMS Meander in 1848, he was a member of the celebrity party that saw Raja Brooke knighted in Singapore on their arrival and Napier’s reputation elevated once more. However, Keppel’s behind-the-scenes activity also was also the cause, unintentionally, of another event in the Palace of Ghosts story. During the stop-over in Singapore Keppel resupplied the HMS Meander and the rest of the party made various preparations for the new colony before completing the voyage. While in Singapore Keppel took the opportunity to acquaint himself in more detail with its coastline and maritime environment. On 30 May 1848, the day after the investiture ceremony of Raja Brooke, he wrote in his diary:

“On the westward entrance to the Singapore river, was astonished to find deep water close to the shore, with a safe passage through for ships larger than the Meander. Now that steam is likely to come into use, this ready-made harbour as a depot for coal would be invaluable. I had the position surveyed, and sent it, with my report, to the Board of Admirality…New Harbour has another advantage over Singapore Roads. In the latter, a ship’s bottom becomes more foul than in any anchorage in these seas; perhaps from the near proximity to the bottom. This is not the case in New Harbour, though which there is always a tide running, while a current of air passing between the islands keeps it comparatively cool”

This natural harbour, soon to become known as New Harbour, and subsequently renamed Keppel Harbour several decades later, is located between the coast of Singapore Island to its north and the coast of Brani Island and what is now known as Sentosa Island to its south. Shortly after Keppel’s report the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company (P&O), on hearing the news, took possession of the harbour. The creation of a port there was transformational for the trade and economy of Singapore. However, that is not the reason why it is relevant to Palace of Ghosts. The two hundred acres or so of land that had been allocated to Temenggong Abdul Rahman at Telok Blangah by the British in 1823 just happened to be situated along the northern shore of the natural harbour identified and surveyed by Keppel.

Two 19th century views of the Temenggong's settlement on New Harbour's north shore

Between the establishment of the port at New Harbour during the early 1850s and Abu Bakar’s accession to Temenggong in 1862, his father Daeng Ibrahim began selling off parcels of the land for the development of the port. Keppel’s report and P&O’s subsequent acquisition and development of the area as a port and coaling station sparked off a real estate boom in the area and it became one of the most valuable pieces of land in Singapore. It was a huge windfall for Daeng Ibrahim and his son Abu Bakar and was one of the many building blocks in the dynasty’s journey to fabulous wealth.

Of course, towards the end of Daeing Ibrahim’s life, the Temenggong family had multiple sources of income, but the real estate boom sparked by Keppel’s original report that led to the creation of New Harbour was a major contributor to the wealth that enabled Abu Bakar to purchase the large piece of land in the district of Tanglin which was to become the Tyersall estate. Keppel, inadvertently via his report, led to the sale of the land in Telok Blangah and the seed money for what was to become the magnificent Istana Tyersall.

Signed photograph of Admiral Henry Keppel with Sir Frank Swettenham, Singapore, 1900

Keppel returned to Singapore in 1900, aged 91, on a personal visit. He had been appointed Admiral of the Fleet in 1877. On the occasion of his visit the Governor of the Straits Settlements Sir James Alexander Swettenham renamed New Harbour to Keppel Harbour in his honour. The area still bears his name today. Sir Alexander Swettenham was the older brother of Sir Frank Athelstane Swettenham who succeeded his brother as Governor in 1901. In later chapters of Palace of Ghosts Sir Frank Swettenham, always a controversial figure then as much as he is now, becomes an important character in the events which were to unfold nearly half a century after Napier’s Labuan misadventure.

Comments

Post a Comment