Every Story Has a Beginning

While Palace of Ghosts makes no claim to be a history of Singapore, it is a Singapore story based on real events, and one that looks beyond the founding narrative of Raffles and 1819. The story begins earlier not to challenge any existing narrative, official or otherwise, but simply because that is where a more logical beginning point exists relative to the linked events that subsequently transpired.

The idea of continuity – the links in the historical chain of events connecting the past to the present and extending into the future - arises time and again throughout Palace of Ghosts. It’s opposite, discontinuity, is an ever-present shadow, lurking in the background. I preferred, however, the notion of erasure over discontinuity as that shadow, because in many unfortunate cases erasure is the cause of discontinuity. But erasure can be a slow process because of evidence that stubbornly continues to exist. In Palace of Ghosts Istana Tyersall and Istana Woodneuk – the two palaces which feature as centrepieces for the story - are part of that evidence. How long they will continue to be so is uncertain. All traces of them seem to be in the process of being erased, through neglect or silence, slowly but surely. The pendulum of time sweeps a never ending arc, casting the dust of times past into a wasted cloud of nothingness, but only if we let it.

Just because there is a gap in the record, an ignored or forgotten piece of history, or a failure to recognise the significance of an historical episode, on purpose or by accident, doesn’t mean continuity failed to occur. What I wanted to do was understand how continuity spanned the founding narrative of Singapore: I was simply not convinced that Raffles nor 1819 could be called a plausible or convincing “beginning”. Of course it is reasonable to argue that armed with 100% of the information there could be no “beginning”: what I was therefore looking for was a better inflection point – one that would have more relevance to subsequent events than Raffles and 1819 could offer. And to do that I had to have a better perception of what was going on in the region in the second half of the 18th century that could be linked to what was eventually built at Tyersall Park.

One of the themes of Palace of Ghosts seeks to embrace is not only the interruptions to continuity caused by intentional or unintentional erasure, but in fact the paradox of continuity and erasure. Any story is a sequence of events, like the links in a chain. Often, we find in history that some of those links are missing: forgotten, erased or ignored. Whether purposefully or inadvertently the net effect is that they become lost, sometimes temporarily, sometimes permanently. It is fair to argue that there is no way we could know if an episode had been lost permanently, except that there would be a gap, an unexplained blank in the record. One might sense, intuitively, that something should be there, but you just wouldn’t know what it was.

In the last couple of decades there have been many assaults on the notion that 1819 was the beginning of everything in Singapore. All of them seem to express indignation at the very idea that there was virtually nothing going on in Singapore at the time. Then Raffles showed up, took over the unused and supposedly unoccupied piece of land and put it to good use, with the eventual outcome of what we see today. It is apt that the stylised image of Raffles represented by the statue that we see today in Empress Place, Singapore, where Raffles allegedly first landed is as inaccurate as the idea that up until 1819 Singapore and what historian Dr. Leonard Andaya calls the surrounding “Negara Selat” – the Realm of the Straits – was unused, unimportant, or unvalued by the people who lived thereabouts.

Every story must have a beginning. For Palace of Ghosts the beginning is not a date, nor even a person nor place, but a way of life. I chose a “world” for my beginning. This was partly because records that might document the former three historical waymarkers are far from reliable. It is, and was, an unfamiliar world to contemporary westerners and Asians alike, but comprehending it even a little is the best way to put a mental framework around what happened subsequently.

This world is essentially a cultural context: a set of traditions and societal norms, that created the circumstances for an individual named Temenggong Daeng Abdul Rahman bin Tun Daeng Abdul Hamid, known in the book as Temenggong Abdul Rahman (1755-1825), to be in the right place at the right time. He wasn’t there, milling around by the side of the Singapore River, in February 1819, clipping his toenails and waiting for a coconut to fall from the tree. Monumental political upheavals and an important sequence of events had caused him to be there. It was among those sequence of events that I searched, therefore, for the inflection point for the beginning of the story of Palace of Ghosts.

A Temenggong is a Malay and Javanese title of nobility, considered to be within the top three aristocratic rankings. He, and it was always a male, was responsible for the security of the monarch, in this case the Sultan. The world of the Temenggong, rather than the Temenggong himself, is the starting point for Palace of Ghosts because the lingering memories of what that world represented account for many of the decisions made and events that occurred even centuries later. Even today we hear comments from contemporary politicians that harken back to those times (see https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/ex-pm-mahathir-says-malaysia-should-claim-singapore-and-riau-islands). Of course, prior events very often explain subsequent outcomes. In this case those outcomes occurred when it appeared that all traces the world of the Temenggong had been utterly swept away.

However, the significance goes deeper, much deeper. On the global stage Singapore is a shining star of how things should be done. It is successful, efficient, green and clean. It is an enviable example of optimal urban living that city dwellers the world over aspire to. Sniping critics should come and have a look at how life is here. Yet its population, even its politicians, say they feel vulnerable and lack confidence. It is because they are disconnected with history. Few people, including residents of Singapore and its immediate hinterland, think, or know, about the fact that there is a continuous arc of history that stretches back hundreds of years and that Singapore today is only the most recent manifestation of that legacy.

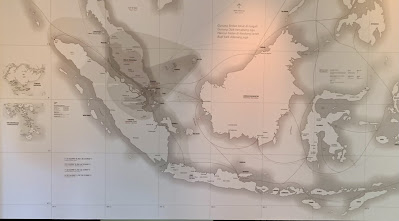

The flurry of books in the last few years say that we should stop thinking about Singapore’s beginning being in 1819, and in fact recognise that archaeological evidence of a royal settlement there 700 hundred years ago exists. Not only that but the 700 year old kingdom has a mythological provenance that, despite the biological challenges of gods and humans interbreeding, somehow includes ancestry linked to Alexander the Great. Fantastic! But what about the 400 or 500 years in between. The problem is geography, more specifically modern political geography. If you see the region through the lens of modern nation states, then you naturally focus on the island of Singapore. This lens is almost as modern as the contemporary miracle of Singapore: a more preceptive spyglass is required. One that can focus on how the Temenggongs thought about their world.

The relevant predecessor of Singapore was not the 700-hundred-year-old kingdom that archaeologists’ uncovered at Fort Canning during the 1980s. Nor was it Alexander the Great’s mythical descendants. The predecessor of Singapore were the ports of the Johor-Riau Sultanate, most significantly the Port of Riau located on west coast of Bintan Island about 30 km to the south of Singapore. Strip away modern perceptions of geography and a clearer view of the past emerges. It is not unusual for notions of geography to hide historical reality. London, for example, was not always the capital of England: and England was not always what it is today. Understanding the provenance of Singapore means looking beyond our modern-day constructs of territory and boundaries.

The world of the Temenggongs is the connection, the portal, to that history. Modern Singapore did not inherit its mantle of success from the 1960s People’s Action Party, nor from its days as a British Crown Colony, nor as a trading hub of the English East India Company but from the ancient Sultanates whose history stretch back many centuries before, perhaps even connecting to the times of Fort Canning’s archaeological discoveries. That would be a seriously long story arc, with many gaps, and certainly beyond the scope of Palace of Ghosts.

A Sultanate is of course a political construct. It’s the people who lived there, why they lived there and what they did which is where the real significance lies. It was one of the most multicultural societies that has ever existed on earth. Peoples from the vast Southeast Asian archipelago: Malays, the Orang Laut, the Bugis to name just three - there were many others. Asians from China, Japan and India. People from further afield such as Arabs, Portuguese, the Dutch and English. They all converged on the same spot because of its unique geography and meteorology. Give or take a shifting location, since this culture was not necessarily anchored to a permanent land base, it was a wealthy, multicultural society, exploiting the latest in trading technologies to take advantage of the exceptional geographic and maritime location. Sounds familiar? That is because it is: Singapore today is the latest in a succession of trading hubs that existed 250 years ago and for many centuries before that. These hubs moved around the locale just as the mindset of their ancient occupants also tended to. Today Singapore is an updated expression of that ancient way of thinking.

The starting point for Palace of Ghosts is therefore the period that hosted the trading hub that existed prior to Singapore or, more specifically, its fall. It was the collapse of the port of Riau which led to the creation of the next trading hub in the Negara Selat. Not Raffles. Not February 1819. This is the moment in time that is the beginning of the story of Palace of Ghosts.

Comments

Post a Comment